The Joyce Theater, New York, NY

March 23, 2023.

The easeful effervesance of Esplanade, the communal vibrancy of the concluding section in Revelations, the sweet frontier spirit of Appalachian Spring: I’d defy anyone to say that joy and heart don’t have a place in concert dance. Yet, I sometimes feel like postmodern dance has gotten disconnected from how powerful such kinetic joy, and pure wholesome feeling, can be.

Parsons Dance’s 2023 Season at the Joyce offered that in spades. In particular, Artistic Director David Parsons’ keen musicality and poignant use of kinetic metaphor brought such joy and heart to full life. Guest Choreographer Rena Butler’s piece brought together attuned movement vocabulary and skillful building of atmosphere to create a similar effect.

In addition to the works described below, I enjoyed seeing Caught (1982) and Balance of Power (2020) once again (I reviewed the company in 2021). Pieces previously in the program had turned my gaze toward joy, and I saw that in these works even more than I did then. In Caught, Zoey Anderson brought an easeful confidence to her powerhouse virtuosity.

Croix Diienno’s confidence in Balance of Power, similarly supported with striking virtuosity, even had an element of coy and sass. Anderson and Diienno also executed Parsons’ exemplary musicality to a “T” – something I also saw more on this second viewing. It made me smile to experience just how much of a blast (it seemed like) these stellar soloists were having while performing.

The program opened with Swing Shift (2003), a compelling work that set the tone for the program to come: of memorable performance, fresh choreography with stellar musicality and a rich emotional landscape – yet one in which heart ultimately prevails. To begin the work, an ensemble built from one to eight dancers.

Athleticism also gradually built. It was never virtuosity for virtuosity’s sake, however — never exhibitionist, always fueled by meaning or serving to deepen the atmosphere at hand. In fact, clear from this very first work was Parsons’ ability to seamlessly blend the codified and the pedestrian, the technical and the more universally human.

The ensemble also executed that vocabulary in ways that keenly embodied the textures and tones of the live instrument (or instruments) accompanying them — the pluck of the cello, the unique resonance of the violin. Movement also oozed with feeling. One section reflected whirling dervishes, dancers seeming entranced in music and circular, repetitive movement.

A palpable shift in the emotional life came later in the work, to something softer and more reflective — with melty movement and somber undercurrents in the score. As energy picked back up toward the end of the work, frequent formation shifts reflected lively communal life. Dynamism was the name of the game. At the same time, the power of the subtle was not lost, down to glances and soft gestures.

The work ended with all dancers but one dancing off stage. Right on beat, one of them reached for the dancer still on stage – who leapt, with elan, to join the group. In joyful, truly unified community, no one is left behind. This ending also set a precedent for the program to come — of clever, innovative endings, within an art form where many endings can feel quite “done before.”

Mr. Withers, premiering this Parsons run at the Joyce, came right before intermission. A standout for me in the program, the work is an Exhibit A of how intentional shaping and placing of bodies in space can speak in fully unparalleled ways. The work felt more specific in terms of narrative than much of Parsons’ work, perhaps as a result of a choice to bring the stories of Bill Withers songs to kinetic life. Whatever the reason, that specificity simply worked for me, leaving me thinking but also heartbroken in the best possible way.

Consistent with notable accomplishments in the program overall was the work’s stellar musicality, both in Parsons’ vocabulary and in the ensemble’s execution of it. Most salient in how movement met music, however, was a specific choice (or choices) in each section that enlivened the Bill Withers song at hand. For example, to “Grandma’s Hands,” dancers surrounded one ensemble-mate with outstretched fingers – of hands that came to lift, rotate and raise up that one dancer.

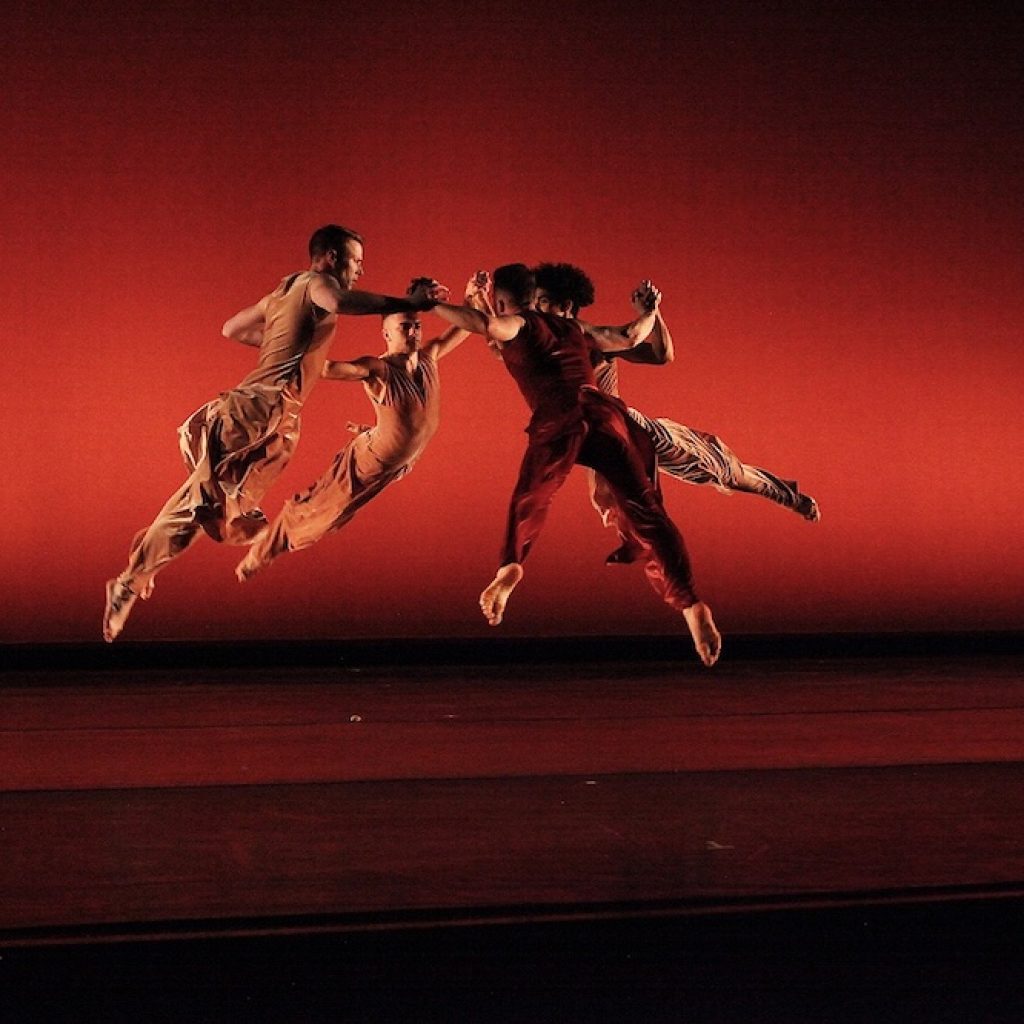

In a section describing a heartwrenching tale of a Vietnam shoulder wanting to communicate with loved ones back home, dancers in silhouette – across a red backdrop (lighting by Christopher S. Chambers) – moved slowly, in unison, as if marching. Certain personas in this tale came forward out of silhouette, and moved in more individualized ways. Through illuminating them, they became much more than a statistic – a human with a story all their own.

The iconic “Lean on Me” included partnering sweet, kinetically attuned and aesthetically rich – all at once. In turn, ensemble members supported and were supported. Mr. Withers was more poignant and heartfelt than joyful, per-se. Yet, in that heart can be its own kind of joy, that of the capacity to deeply feel.

Right after intermission came Rena Butler’s The Ride Through, also premiering in this run at the Joyce. It’s a work that offers full menu of dynamics and tones, from funky to spiritual to primal. Through all of those modes of being and feeling, and also par for the course with this program, choreography translated the score (from Darryl J. Hoffman) into cogent physicality. While Mr. Withers rested on a foundation of narrative and ideas made physically tangible, this work placed atmosphere and aesthetic front and center. Both offerings are valid and meaningful in their own ways, if executed well – as they were in this program.

An early section had rolling hips and shimmying shoulders – from an ensemble oozing sultry, confident cool – filling the air with funk. Cohesion and ease, in and out of partnering vocabulary, bolstered that sense of funk. A notable shift in tone came soon in the work, however – building something softer and more spiritual, imbued with divine grace (or at least seeking that).

The only light came from offstage, and dancers moved toward it – like moths to a flame. They also danced as if overcome by its power, as if moved by an external source rather than moving, absorbed and entranced. That absorption soon shifted into something more animalistic and primordial — the movement muscular, but at the same time sinuous and serpentine.

The overall atmosphere followed suit – the score filling with polyrhythmic drumming, for example. Perhaps these three modes in sequence told a story of a journey of being, in the body and beyond. The thoughtfully-crafted movement and memorable atmospheres at hand were also more than enough to satisfy. That can be its own kind of joy and heart.

Closing out the program was Nascimento (1990), also premiering in this run at the Joyce. The work presented all of the bold movement vocabulary and excellent musicality, as well as the capacity to deliver something so simple yet so very rich, that were on offer throughout the program. The work brought to the stage infectious joy and sweetness, to boot. Bright colors across the stage – from lighting (from Howell Binkley) to costuming (from Barbara Erin Delo, original costumes by Santo Loquasto) laid a firm foundation for that sort of brightness and joy. Latin dance footwork early in the work, danced with sassy ebullience, laid more stones on that foundation.

The score, for its part (from Milton Nascimento), brought more brightness. At the same time, there was melancholy underlying the singer’s voice – the kind resonant through joy layered over past sadness. Experience is what truly blooms artistry, that of the dark and the light. For all the joy in the piece, in the kinetic and beyond, that undercurrent of sadness, of thoughtfulness, kept it all feeling measured rather than saccharine.

That Latin dance party vibe moved into various other atmospheres, which Parsons structured to feel just long enough — enough to sufficiently build but not so much as to drag on. In particular, one section a movement phrase repeating enough to build a meditative feel – but not so much as for it to get tired.

In moments of pure vibrancy, dancers leapt straight up – with arms reaching toward the heavens and their legs meeting high toward the side. I wanted to leap with them and find the same flight, the same freedom. To end, the dancers held hands in a horizontal line across the stage and walked upstage, backs to the audience. United, what they had offered was enough – more than enough – because it was full of joy and honest feeling.

Shining a light on life’s sorrows and trials more than has its place; our heads floating in constant sunshine and rainbows is only harmful self-delusion. Yet, joy and connection are just as important – and, especially because they co-exist with those sorrows and trials – are something to celebrate. Thank you to Parsons Dance for leading such celebration, with notable facility and commitment, and therein reminding us just how special the joy and heart within dance can be.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.