When you think of “dance”, do you think of people moving in public, captured on film, and widely disseminated over the internet for public consumption and experience? Most likely not; you most likely think of people seated quietly in a theater, watching dance art happening live on a professionally-lit stage. If we’re honest about socio-economic and cultural realities, it’s most often only a certain type of person seated in that audience. Sarah Elgart, choreographer and founder/director of the Dare to Dance in Public Film Festival (D2D) is out to change that.

D2D has occurred annually through the online arts and culture magazine, Cultural Weekly, for three years. In 2019, it will also be presented at REDCAT (a part of Disney Hall in Los Angeles) — at the invitation, and as part, of Dance Camera West’s annual festival in January of 2020. It all began after Elgart, a choreographer and director working under the auspice of Sarah Elgart/Arrogant Elbow, left her position at Dance Camera West, where she had worked for nearly seven years. A friend of hers, Adam Liepzig, publisher/managing editor of Cultural Weekly, invited her to come on board as a regular contributor.

Thus, she began her column, ScreenDance Diaries (now in its sixth year), that focuses on the intersection of dance and film. Around two-and-a-half years after beginning the column, Elgart had an idea for expanding the community of dance film makers as well as using the platform she had created with the column — to create an online dance film festival. With Leipzig in full support of the idea, D2D was born.

For years, Elgart has created site-specific dance works in non-traditional places as diverse as airports, bus terminals, office buildings, museums and more. “So often, when people see dance in a public place where they don’t expect it, they see something that they didn’t know existed,” she explains. “I thought, ‘What if we could do that with an online dance festival? What if we celebrate dance in public?’ So often, when you say ‘dance’, people think classical ballet or tap, but we show them that’s only a small piece of what dance is and can be.”

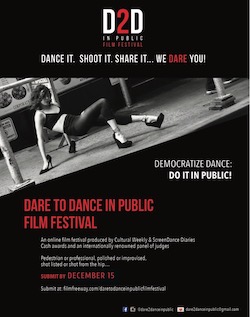

The festival places the internet as a platform to spur a conversation around dance, as well as making great dance films in public space. “Our motto is: dance it, film it, share it,” Elgart adds.

That spirit of accessibility and openness lies at the heart of the festival — promoting a broadening of the playing field and an experimental spirit at the intersection of dance — done in public — and the camera/film. “It invites dancers, choreographers, filmmakers and non-dancers alike to challenge the idea that there is a right time and place to dance,” Elgart describes. “Whether it’s dance happening in parking lots, supermarket aisles, train stations or city crosswalks, it’s about sharing the power of dance as a life force and how it connects us as people regardless of our background.”

Anyone is welcome to submit a work. The submission deadline for the 2019 festival is December 15.

Winning films receive cash prizes and coverage in Cultural Weekly. The online publication has approximately 30,000 subscribers, offering the D2D festival the potential to reach such a diversity of people and accomplish such sharing, challenging and connecting. The public screening at REDCAT can only bolster these means to these ends, as well as offer a tangible space for community-building around the values of creative openness and sharing.

Additionally, every year, Elgart invites a panel of renowned professionals engaged in the dance and film space. In years past, the panel has included such as notable figures as Desmond Richardson, Vincent Paterson, Julie McDonald, Valerie Faris (co-director of Little Miss Sunshine) and more. This year’s panel of amazing judges — Katherine Helen Fisher, d. Sabela grimes, Benjamin Johnson, Renae Williams Niles, Tony Testa and Elgart — will adjudicate selected works submitted to the festival. Submitting a work to be shown in the festival “has an added bonus of having these panelists see your work,” Elgart says.

She goes on to describe the geographic, cultural and stylistic diversity of works that have been submitted in past and current D2D festivals — from Butoh-informed work, to the flavor of contemporary dance often seen in Europe, to street dance and contemporary dance blends. Sponsors of the festival to date have included MSA Agency, Go 2 Talent Agency, Anita Mann Productions, Dance Gap Year and many more. D2D is currently looking to bring more sponsors and collaborators in the future, Elgart says.

Why, more specifically, promote dance in public space? For one, bringing the art form out of a proscenium setting and into public space dramatically boosts access to it, Elgart asserts — in other words, democratize it. That happening has a secondary meaningful effect; it expands comfort with movement, and dance art, she believes. This effect can be a powerful force in demystifying dance for the wider culture out there.

Elgart describes a potent example of these effects, when she brought a “roving site-based” work — meaning the work moved locations at the site several times — to Jacob’s Pillow, staff were a bit anxious about moving a reasonably large audience several times (given concerns with safety and logistics). Yet the audience was entranced, Elgart recounts. “They stayed and spoke with myself and the dancers for over a half hour following the performance, sharing their impressions, their thoughts and memories of theirs that the work (entitled Shape of Memory) evoked in them. She underscores how dance taken off a stage and out into public space can viscerally engage audience members because “they’re part of the work… inside of its physical space, making the work less distant or aloof.”

Why dance on film (aka screen dance)? With the ability to shoot multiple takes, as well as editing tools, creative possibilities abound — arguably, even more than they do in concert dance. The ability to watch segments or whole works over again is another advantage. Going back to that idea of democratizing dance, “we all have smartphones now,” and we can all watch or create as much dance as many times as we can and want, Elgart affirms.

Some may argue that dance on film can’t capture the same ephemeral magic that live dance can. Yet Elgart holds that dance on film, when crafted with skill and thought, can offer a different kind of magic all its own — capturing the sounds of breath or foot work, the ability to invert and/or repeat time, the ability to get very close to and/or inside of movement, and much more. For those interested in creating dance on film, Elgart advises starting by viewing a good deal of the form oneself.

She hopes to see D2D grow in subsequent years, such as possibly touring with it (adding dates in additional locations). She believes that screen dance as a genre will become more well-known, more commercially viable as an entity and more common worldwide. “In this age of social media, we’re all sharing our experiences all the time,” Elgart says. To her, dance and movement is just an extension of the experience of living. It seems that dance on film is a natural intersection of moving through the world, in one’s unique experience, and then sharing that experience in a way that’s accessible to others. D2D is at the forefront of this meaningful, forward-looking space.

For more information on Dare to Dance in Public Film Festival and how to apply, visit www.culturalweekly.com/dare-dance-public-film-festival-round-3.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.