On the August 22nd edition of Good Morning America, Lara Spencer reported on Prince George’s school curriculum. After noting that the young royal is taking ballet, something his father Prince William has said that he truly loves, she said, “We’ll see how long that lasts.” Spencer laughed out loud, and the in-studio audience joined in. The dance community did not take these comments and laughter lying down. Noted dance professionals from Travis Wall to Christopher Wheeldon to Ashley Bouder weighed in on what happened. They identified her comments as bullying, as well as noted the gifts and graces that the study of ballet (as well as other dance forms) can confer.

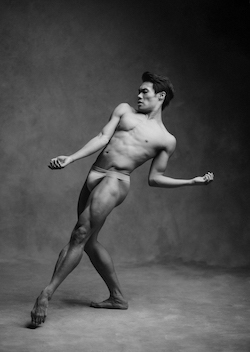

Others, including Benji Schwimmer, added nuance to the conversation by injecting discussion on privilege, sexism and related matters in dance — for instance, the fact that most leading choreographers are men, even in a female-dominated field, and that Spencer herself is a woman in a field in which being one isn’t so easy. Nevertheless, the hashtag “#boysdancetoo” trended. On September 2, over 300 dancers — men, women and those from all along the gender spectrum — attended a ballet class in Times Square, outside of the Good Morning America studios.

Gia Kourlas from The New York Times and Sarah Kaufman of The Washington Post wrote editorials calling for more awareness and respect toward the dance community. Spencer did make public apologies, first on social media and then on air (even sitting down with the prominent male dance dance artists Wall, Robbie Fairchild and Fabrice Calmels). Some in the dance community expressed gratitude, some said it was too little, too late, and others offered reactions somewhere in between.

All of that considered, we at Dance Informa always seek to be as practical and positive as possible. We’d like to take this opportunity to discuss how to support young dancers, and young male dancers in particular, who often experience bullying. To learn more here, we spoke with Rennie Gold, director of The Gold School; John Lam, Boston Ballet principal; and Erica Hornthal, Chicago-based LCPC (Licensed Clinical Professional Counselor), BC-DMT (Board Certified Dance/Movement Therapist).

Make your studio as gender-neutral as possible.

Gold discusses ways that he makes The Gold School “boy-friendly”, in contrast to many other studios he’s seen. For instance, decorations have much less “frill” and pink coloring. Gold and his staff also shop for costumes for male students at conventional clothing stores, versus from dance supply stores. “Often, costumes for boys from these companies look very similar to those for girls,” he says.

Hornthal carries this idea of gender-neutrality in the studio even further. She suggests coloring of whites, blacks and greys versus pinks and blues, and some gender-neutral images such as nature scenery and inspirational quotes. “The image of a ballet dancer is a ballerina,” but studios can help young male dancers see themselves as dancers by decreasing the femininity in imagery around ballet and dance more generally, she believes.

She also recommends using educationally-based classical music scores for class music, versus music that feels very light and airy — and hence, to some young male dance students, perhaps a bit feminine and unwelcoming. On a larger level, Hornthal encourages dance educators and others involved adults (such as parents, teachers and school educators) to ensure that young people have a space to explore themselves and their interests through movement. Perhaps that’s dance, perhaps it’s a sport, perhaps it’s a martial arts form. The important thing is for young people to have agency to find what interests them and pursue those interests. That certainly includes young female dancers as well, who have their own notable personal challenges when it comes to growing up in dance and other movement forms — such as perfectionism, body image issues and “fitting in” with other communities of young people.

Ensure that young dancers have a support system, role models and adults who act in accordance with their best interests.

Gold discusses how in his middle school years, when he was experiencing bullying (verbal and physical) for dancing, the studio was his “safe-space”. The worst bullying occurred when he moved to a new school district, he explains. His peers where he had lived had come to accept his dancing and didn’t make any big thing of it, but not so much those in his new school. It seems that adults in young male dancers’ lives should regard such a change in environment as something that could lead to bullying, and should therefore stay attuned to signs of bullying — avoidance behaviors, apparent drops in self-esteem and even signs of physical abuse (torn clothes, bruises, broken skin) — when such a change of environment occurs.

Many times, Gold almost quit dancing, but his mother, Sherry Gold (founder of The Gold School), wouldn’t let him. He had a teacher who would let him stay in his classroom after school, until all the other kids (some of whom had bullied Gold) had left. At the same time, the teacher did nothing to address the main issue — the bullying. Gold does believe that teachers who did just that would have made a difference for him.

It also would have meant something to have more male dancers at his studio, he says. He and the male dancers who were there did become a support system for one another. For this and many other reasons, he’s consistently working toward having more male students at his school. It also helped Gold to have successful male dancers to look up to. His mother would perform a good deal, and travel with him to many dance conventions and other events, giving Gold an opportunity to meet professional male dancers and see them at work. “I wanted to be like them, and that helped keep me going,” he explains.

Lam describes being bullied as well. “I made it, I kept dancing, but many others unfortunately don’t.” He believes that a certain level of having “thick skin” has its place, in the sense of living in a way that’s true to yourself and not letting others’ cruelty change you or your behavior. He agrees that doing that can be quite different than complicity in such cruelty. He underscores the truth that “you can’t control others’ thoughts and actions, only your own.”

As another practical approach, Hornthal emphasizes how bullying is often about the bully, rather than the bullied; insecurity and other personal mental health struggles can lead people to seek power over others through bullying. Thus, for caring adults in the lives of a young child who is being bullied, an effective route to stop (or at least lessen) the bullying behavior might actually be advocating for addressing the needs of the bully or bullies — which could be professional mental health treatment.

Hornthal also advises truly believing in young dancers, be they male or female. Household names such as Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and Mikhail Barishnykov were once in their place. “Who knows,” she says, “that young dancer could be the next big dance name!” Believing in young people can help give them the validation and confidence that they need to push forward toward their dreams in the face of adversities like bullying.

Act locally, think globally. Work within the dance world, but keep in mind that bullying and extreme gender normativity, and mental health more generally, are much bigger social problems.

Lam emphasizes how much of the problem of male dancers getting bullied (and the mental health issues that female dancers encounter, in different ways) are larger social problems that are beyond the dance world to solve. “Society presumes roles we should fulfill, without understanding people’s place in the world and the conditions they experience there,” he asserts. He concurs that many people out there see things in binaries, rather than somewhere along a fluid spectrum.

Gold cites clear examples of these dynamics at work in microaggressions he’s encountered, such as when he tells people that he’s a dance educator and the response is, “Oh, I always wanted to have a girl so that I could put her in dance class.” Lam believes that people have good intentions at heart, and just need to learn as well as be more mindful. He promotes traveling the world, as much as possible within individual life circumstances, to open one’s mind and meet all sorts of people. He also believes in educating young people and exposing them to the world, yet doing so in age-appropriate ways.

Lam believes that leaders in politics, business and other sectors — yes, including the arts — are also quite influential here. He agrees that dance can act within its own limited sphere to make a difference in the wider world. As an art form concerned with the body, its conventions and its new possibilities, dance can be a force to push against the rigidity and ubiquity of gender norms. Indeed, “ballet is beginning to defy many norms, particularly with men,” Lam believes.

Hornthal also surfaces the matter of addressing mental health issues within the dance world, beginning with breaking down stigmas and moving into making evidence-based treatments widely accessible — a model for culture at large addressing its mental health crises. “We can do what we do, but think bigger,” affirms Lam.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.