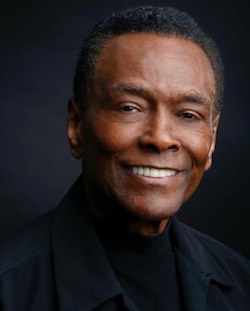

Close your eyes for a moment, and visualize a ballerina and a danseur dancing a pas de deux. Are they black? Chances are, they’re white. While there are larger cultural and psychological forces at work there, in the past and today, Arthur Mitchell – who called himself “the Jackie Robinson of ballet” – spent his career chipping away at the powerful image of ballet dancers as white. He had a mission to prove African-Americans can capably dance classical ballet, just as much as those of other races can. Mitchell passed away on September 19, 2018, at 84 years of age, from renal failure, shared his niece, Juli Mills-Ross. George Balanchine saw in Mitchell enough to disregard racist backlash to his dancing top roles for New York City Ballet (NYCB), leading him to be the first African-American principal dancer to gain international fame. He danced for NYCB from 1955 to 1968, when he branched out to tour internationally. He then soon co-created Dance Theatre of Harlem.

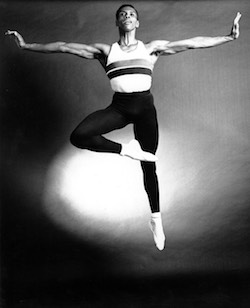

Arthur Mitchell. Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

Yet, as Sarah Halzack describes in The Washington Post, Mitchell wanted to be regarded for his own ability, rather than as a “token” African-American in ballet. Jennifer Dunning of The New York Times recounts how Mitchell “displayed a dazzling presence, superlative artistry and powerful sense of self.” He received numerous honors over the course of his career, including a Dance Magazine Award (1975), a Kennedy Center Honor (1993), a MacArthur “Genius” Grant (1994) and the National Medal of the Arts (1995), shares Dance Magazine.

Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934, to a father who was a building superintendent and a mother who was a homemaker. He grew up in Harlem singing in a choir, taking tap dancing lessons and learning social dance. When dancing a Fred Astaire-inspired routine at a school party, a teacher suggested that he audition for the High School for the Performing Arts in Manhattan. He worked incredibly hard there, and soon enough had reached a pre-professional level of technique and performance ability.

Mitchell turned down a chance to study at the acclaimed Bennington College modern dance department, opting to instead study at the School of American Ballet, despite being told that he didn’t have the right skin color to have a successful career in ballet, shares Dunning in the Times. Defying these presumptions, “he performed in Europe and the United States with Donald McKayle, Louis Johnson, Sophie Maslow and Anna Sokolow, and he played an angel in a 1952 revival of the Virgil Thomson/Gertrude Stein opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, in New York and Paris,” recounts Dunning. Mitchell was also beginning to choreograph and make his own work. While on tour in Europe with John Butler Dance Theater, he got a call that George Balanchine wanted to hire him for NYCB.

His first major role in the company was replacing Jacques d’Amboise in Western Symphony. Mitchell reported that he heard many gasps, and at least one racist comment, when he stepped out on to the stage for the role for the first time. Balanchine was soon making works on Mitchell, including his signature roles of Puck in Midsummer Night’s Dream (1962) and the principal male role in Agon (1957), despite these racially-based reactions. With the latter, he danced a duet with a white woman – an incredibly provocative creative choice at a time of incredibly high racial tension in America. Dunning (at the Times) described how the pared-down aesthetic of black and white costumes, those shades intersecting in the lines of movement, reinforced the provocative (at the time) nature of the duet. Balanchine himself got several letters taking issue with Mitchell in such roles. The iconic dancemaker persisted in giving Mitchell the roles he had the talent to dance.

Apart from a lovely and unique aesthetic as a dancer, Mitchell was a commendably hard worker and quick study at picking up roles. Mitchell once said that it wasn’t about what role he would dance; rather, he would say, “What would you like me to do? Use me.” He left NYCB in 1968 to make work, and work toward making companies, in Italy and Brazil. That was all until – again, while touring – Mitchell learned of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in 1969. It inspired him to do the most he could do to realize Dr. King’s “dream” – to create a dance company that would nurture and spotlight African-American dancers.

Mitchell once said that at that point, he thought, “I could wait for others to change things for black Americans. Here I am running around the world doing all these things — why not do them at home? I believe in helping people the best way you can; my way is through art.” As such, Mitchell formed the school and company of Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) with his mentor, Karel Shook. It all began modestly, with two students in a garage. Within months, however, he had over 400 students. Some called him “the pied piper of dance” because of how he could draw students in to his classes, despite a reputation for being quite a strict teacher.

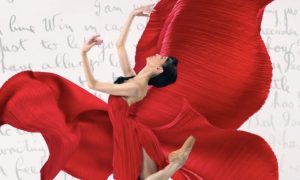

Arthur Mitchell.

The performance company of DTH grew to have international acclaim. Dunning shares how “in a review of a 1970 performance, New York Times dance critic Anna Kisselgoff called the company ‘one of dance’s most promising ventures’ and wrote, ‘No young company has made such progress in so short a time.’” Big names, including Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, contributed to DTH’s early repertoire. The company toured in Italy, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, South Africa and England. Its first full seasons were in New York City and London in 1974. Mitchell shifted away from choreography, to focus on assembling a diverse repertoire, including classical and contemporary work, as the company grew.

Despite public and critical acclaim, from 1990 to years after that, DTH faced financial trouble. Corporate sponsors pulling out and government fiscal support led to the company having to lay off dancers and staff, in 1990 and in 1995. “In 1997, dancers went on strike, and more fiscal woes followed in 2004, when the company rang up a $2.5 million deficit,” recounts Halzack (WaPo). Through all of that difficulty and a brief shut down (for restructuring), DTH is still carrying out its mission and vision. The company has been under the direction of Virginia Johnson since 2009, and will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, shares Courtney Escoyne at Dance Magazine. Today, DTH is still a predominantly African-American company but does include dancers of all races.

Mitchell stepped down as the company’s artistic director, becoming artistic director emeritus, in 2011. Still, DTH has gone forth in the spirit of its mission, a spark that Mitchell set. This past January, Dance Magazine asked Mitchell if he thought his dreams for the dance world had come to fruition. His response – “Name all the companies in America. How many have a leading African-American ballerina? There’s only one in a major company, that’s Misty Copeland in American Ballet Theatre. There’s still work to be done.” Yet it seems like the viability and accessibility of the arts, race aside, was also incredibly important to Mitchell; “anyone living without the arts in their lives is living in a desert,” he once said. His life’s work undoubtedly allowed many people – many African Americans, but many of other races as well – to come to an oasis of experiencing the art of dance.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.