In 2003, Dana Tai Soon Burgess created a work on an immigrant experience that his own immediate family members experienced — coming to Hawaii from Korea to work on sugarcane and pineapple plantations. In 2018, with all of the heated socio-political discourse around immigration, he decided that it was a good time to refine and bring back the work. “With the work, I want to express how difficult it can be to come to a new country,” he shares. His company, Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company, will perform the work, called Tracings, in the Robert and Arlene Kogod at the National Portrait Gallery on May 4. Burgess is the Smithsonian Institution’s first ever Choreographer in Residence.

The Kang family pose on the Del Monte plantation where they worked. Photo courtesy of DTSBDC.

Dance Informa spoke with Burgess about the process of bringing this repertory work back again, personal meaning of the work for him, aesthetic influences for the work, and more. He describes how he “edited” a lot in the work, paring down to essentials, for this revival. There were also considerations for performing the work outside, such as changing the backdrop. Projections during the performance will display the Korean-American experience on Hawaiian plantations. The National Portrait Gallery is also currently exhibiting “Portraits of the World: Korea”. Works in this exhibit, and Yun Suknam’s work “Mother III” in particular, set a meaningful, inspiring context for the work to be performed. Thus, the timing worked out extremely well to have the site as a performance venue for this work.

Burgess also details some of the inspirations for movement content in, and aesthetics of, the work. He describes scars on his mother’s hands, which he would ask about when he was a child. In an as age-appropriate way as possible, she told Burgess about working on pineapple plantations when she first came to America (Hawaii, more specifically). The hands thus became a focus in the movement. He recounts how remembering these scars, and the stories she told him about how she got them, was an “ah-ha” moment for him in creating Tracings. His mother, visual artist Anna Burgess, will have an actual physical presence in the work, as well; she will appear as a special guest performer.

For Korean immigrants working on these Hawaiian plantations, the conditions were brutal — long days carrying loads of fifty-pound bags, in the scorching heat. All factors considered, it was essentially indentured servitude. Burgess also asked himself, as if trying to get a sense of the physical experience of carrying those bags, how many of the props shaped like pineapple tree branches would equal fifty pounds. This got him thinking about new ways to use those props and to physicalize the idea of a heavy load upon oneself.

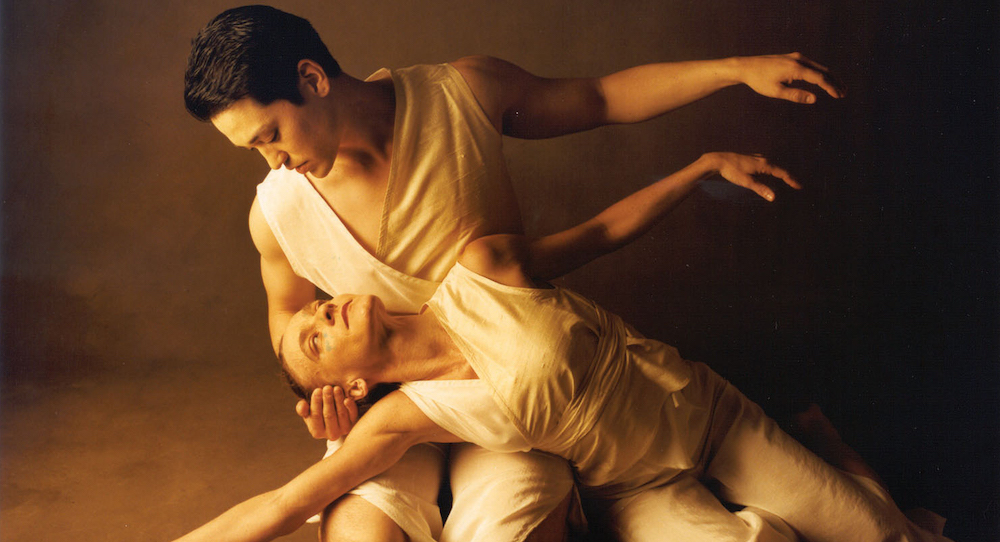

Aesthetically, Korean traditions guided Burgess. For example, he used more Korean traditional dance than he has in most of his works, blending it with contemporary dance, he explains. Costumes are also off-white, a cream color — the color of mourning in Korean customs. The idea of mourning fits into the work in the sense of losing one’s old home and the life one knew when moving to a whole new country. Larger themes like loss, finding love, and building community also guided the structure of the work, as well its movement. Each section of the work has a focus of these larger themes.

Dancer Miyako Nitadori performs movement from ‘Tracings’. Photo courtesy of DTSBDC.

Also key to the work overall is the idea of memory, as well as that of community — within memory, within the present, and within the future. Part of the immigrant experience that Burgess has wanted to illustrate has been this losing and gaining of different communities. These themes are also universal, however, Burgess emphasizes. “We have all experienced love and loss and change in life, so there’s an entry point for everyone,” he asserts.

For Burgess himself, there was also the fact of the work being focused on painful — even traumatic — experiences for his loved ones. Undergoing the creative process with content holding this kind of meaning for oneself could be very difficult for any artist. Yet he believes it’s all in the timing, in allowing the creative subconscious to reveal when you as an artist are ready to explore such a personally weighty topic.

He gives the example of when he went into the studio to create Charlie Chan and the Mystery of Love, a work centered on personal experiences from his youth, he thought it was going to be a completely different work than it ended up being. When he was ready to make it, it showed itself to him, he explains. One could ask the question if this nation is ready to encounter, and perhaps should encounter, more stories about the immigrant experience. Burgess seems to believe that it is, and should. Conversations can start with stories, and conversations can lead to a better world. Art can indeed be part of making a better world.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.