Citizens Bank Opera House, Boston, MA.

March 28, 2024.

I’ve noticed something intriguing in ballet programs presented in recent years: two hours or so of dance including both classical and more contemporary works, sometimes works uniquely blending the two modes. That allows audience members with varied tastes to get something that appeals to them most. In a wider, perhaps more consequential sense, such assorted programs both preserve the art form’s tradition and offer a platform for work that pushes it forward into a more vibrant future.

Boston Ballet consistently, and thoughtfully, presents such a spectrum of work. Each of the company’s programs offers a new way in which the past and present of concert dance are in dynamic conversation. Carmen did so in a way that reminded us of the art form’s treasures that we may have left behind, and subsequently the way that such treasures can be reshaped and repurposed to keep shining all the brighter.

The two-act program began with Kingdom of the Shades, an excerpt of La Bayadère (1877), with choreography from Florence Clerc (after Marius Petipa). The work was atmospheric, soothing and even meditative. Its beginning set the tone, with a long line of dancers repeating the same traveling movement phrase – until they filled the stage with three diagonal lines of dancers. Benjamin Phillips’ sleek, utilitarian design set them at various levels in space (highest, higher and on the stage itself). Their unassuming white tutus and ethereal drapery infused a sense of purity and poise.

Their movement matched those qualities; even through executing the same movement over and over, they never signaled fatigue. Their tastefully low arabesques and restrained penchés weren’t exactly the height of kinetic virtuosity – but that only served the serene sense here.

I reflected on how the values and standards of performance have shifted over the years. As the technology of the body that is ballet has evolved over the centuries, we’ve upped the ante on athleticism. Yet, perhaps we’ve lost some of that satisfying understatement, the kind on offer with this work. Harmony was the name of the game.

Other sections in the work, if for not as long, employed the same movement mantra approach – with dancers settling into repeated vocabulary. Moving in vertical lines (downstage to upstage), they extended their body’s shapes and pathways through their veils. En pointe with arms in fifth en haut (raised overhead), their lifted sense had them feeling like a chorus of otherworldly beings – very classical in quality, indeed.

A pas de deux and three solos also graced us. Yue Shi, supporting his partner Viktorina Kapitonova, beautifully embodied the score’s crescendo and decrescendo. Kapitonova’s quality, like a feather floating in a soft breeze, also made Ludwig Minkus’ soft, dreamy score wonderfully tangible.

The three soloists (Lia Cirio, Chisako Oga, and Ji Young Chae) danced fully in the spirit of the work. They performed with all the requisite technical strength, of course. Yet, more so, they let the movement itself and the atmosphere at hand do the work. “Pushing it” would only feel out of place in this work. At points, I could even feel a sense of delightful play in their performance.

For audience members who would walk out of the theater to a million notifications, signaling who knows what kind of personal life craziness or unbelievable world news, such ease and calm can be the soul balm that we didn’t even know we needed. Something dazzling, something pure, something soothing — a balm indeed, and a gift in its own way. That’s not something to be fully forgotten as we bring the art form forward.

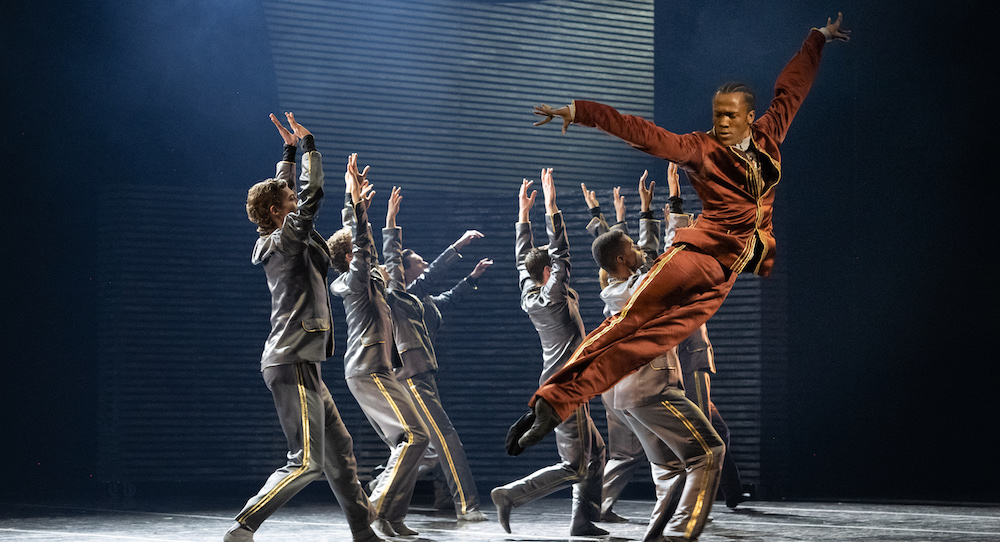

The second act brought a new something, quite different in both tone and style: Jorma Elo’s 2006 contemporary reimagining of Carmen (from Roland Petit’s 1949 premiere). Aesthetically inventive and kinetically bold, it’s an exemplary reshaping and re-envisioning of a classical story ballet for the 21st century. Rather than the gritty streets of 19th century Seville, the story played out on a modern fashion runway. Carmen (Ji Young Chae) was a model rather than a factory worker. Don José (Jeffrey Cirio) was a business mogul rather than rogue soldier, and Escamillo (Tyson Ali Clark) a Formula 1 driver rather than bullfighter.

Production design brought us right into this world of fame and fortune, of magazine centerfolds and flashing cameras. The red color palette in Joke Visser’s costumes paid homage to the iconic imagery of matadors and flamenco. Yet, infusions of purples, golds, and even earth tones widened our lens and playfully challenged our mental images. Bright lights, hung low and shone right into the audience, mirrored the blinding illumination of the runway – and even evoked the sense of being under a critical public gaze (lighting design by Mikki Kunttu).

Elo’s movement innovations – at both the ensemble and singular body level – also shone through. Dancers moving in and out of spotlight, coming into and out of shadow, felt both visually and thematically rich. Vivacious ensemble sections had a crowd moving around Carmen: giving the feel of flattering, yet also unrelenting, attention from fans.

The dancers stayed notably tenacious through long sections of highly fast, athletic vocabulary. Crisp accent gave the feeling of sharp castanet claps. The movement vocabulary, as a whole, rode the resonances and the lively power in Rodion Schedrin’s score (after Georges Bizet).

Part of me did crave more rooting into the stage, movement of a more raw and earthy level. Perhaps the high energy at hand, and the feeling of fame’s freneticism, required a more elevated bearing through the body. Elo called upon the dancer’s voices at one point, having the ensemble joyfully exclaim together. That was also something that I wanted more of; I wondered what it could have contributed as a motif rather than a one-off.

Elo’s building of the three main characters, and how the dancers portrayed them, felt more solidified. Separate sections offered a wide spectrum of qualities and emotional resonances. I thought of the phrase “we contain multitudes” – and these three did indeed. Chae, in particular, brought those varied textures to full life – with equal parts spunk and grace.

Such complex emotional life defies the sometimes reductive labels of hero, villian…and less savory ones slapped on women who dare to follow their own passions. Carmen, as a narrative, has boatloads of raw potential to illustrate that complexity in being human – an illustration perhaps more aligned with modern sensibilities than those of Petit’s time (and certainly Bizet’s). Elo’s version, and how Boston Ballet brought it to the stage, commendably capitalized on that potential. At the same time, it built upon the tradition of this story played out on stages – indispensably so, one could argue.

We can build upon such foundation of the past – with what we’ve learned, with what we’ve changed for the better. To reject either tradition or modernity outright only denies us the magic that can happen when we bring their treasures together. Thank you to Boston Ballet, and all dance companies out there, who continue to do just that.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.