With his New York-based company Periapsis Music and Dance, pianist Jonathan Howard Katz offers a new take on a very old partnership. Music and dance were once inseparable (and in many cultures and communities, they still are). But the codification and commercialization of Western art – from education to venue choices to funding – has driven a wedge between the two. In the past century, live music paired with dance has become a luxury rather than a given. Katz, a composer, teacher, artistic director of Periapsis, and now curator of the new Brooklyn Bridge Dance Festival at GK ArtsCenter in Brooklyn, intends to remove the silos around music and dance and to bring them together in unexpected ways.

Periapsis’ company model is both innovative and simple: employ a roster of musicians and dancers to create a body of collaborative works that values both art forms equally. Founded in 2012, the company set out to support the creation of new music and rarely uses historical pieces. But commissioning composers, says Katz, “is a long-term and very expensive process.” So, in its first few seasons, Periapsis sought out living composers and obtained the rights to their existing music. As the company grew and became more established, Katz doubled down on his original mission and is now focused on facilitating new composer/choreographer collaborations.

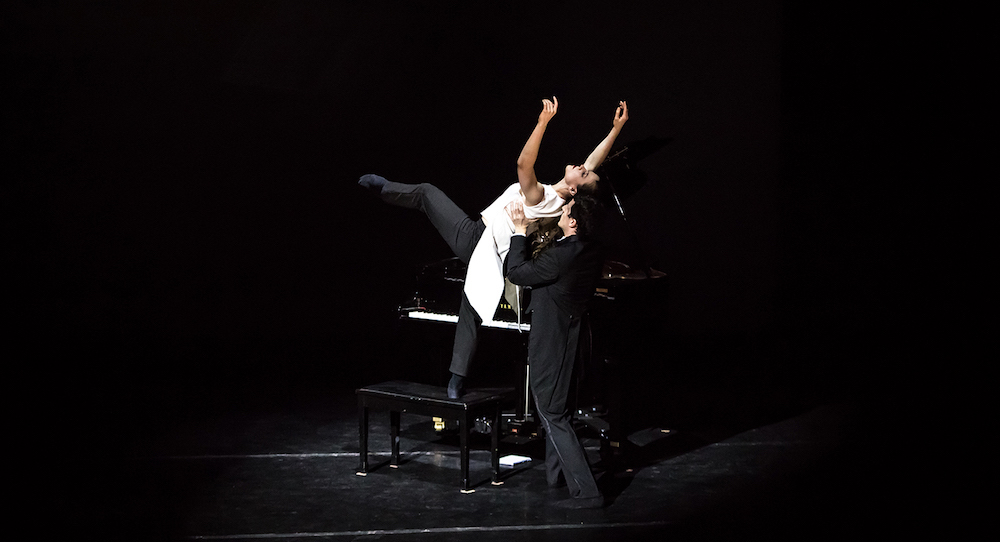

Jonathan Howard Katz. Photo by Rachel Neville.

Many pieces in the company’s repertory, including last year’s The Portrait Project, which paired a composer with a solo dancer and musician, include intimate moments of interaction: a violinist lies on her back, her head resting on a dancer’s stomach as she plays; a dancer confronts a clarinetist and encloses him in a cage of music stands. In June, the company premieres Noesis at the GK ArtsCenter, a work for five dancers and three musicians with choreography by Periapsis resident choreographer Hannah Weber and an original score by Katz himself. He says he and Weber worked in tandem; at times she “choreographed to his music”, at other times he “composed to her choreography”. Katz says he tries not to constrain the choreographer and prefers to let the two elements evolve organically. “When you have dancers and musicians on stage climbing on each other, you’re very conspicuously bringing those two worlds together,” he says, “but maybe it was an illusion that they were so separate to begin with.”

At its core, every art form strives to communicate. “Dance, even in its most abstract versions, has elements of theater, and music has elements of movement,” says Katz. By recognizing the similarities and delving into the differences, artists can enrich their own practice. Initially, Katz was drawn to the grounded, physical nature of dance, recognizing that he “lived in his head” too much as a musician. On the flip side, dancers can learn from how musicians hear rhythm and tempo. When Katz teaches Music for Dancers (he is an adjunct professor at NYU Tisch Department of Dance), he conducts as he plays recorded music, allowing his students to see how a musician’s body responds to the sound’s structure and tone.

Through teaching and curating, Katz hopes to catalyze the dance patron’s appetite for – and even expectation of – live music. He’s bothered when dance uses recorded music “that’s meant to be played live,” and cites the Bach Cello Suites, which are staples of any cellist’s repertoire and widely used by choreographers. (If you’ve ever been to a wedding or seen a commercial, you’ve most likely heard one.) When he hears a Suite played on a recording for dance (which is often), Katz muses, “How many hundreds of cellists are there in New York who could do a great job with this?” He adds that because so many cellists already know the Cello Suites and would enjoy the experience of playing for dance, they might contribute their expertise for “next to nothing”, debunking the theory that live music is too expensive.

To that end, Katz is building an artist resource page on his website. It’s a sort of one-stop-shop for choreographers, musicians and composers who otherwise might not have known how to connect. The page includes a growing composer list (currently at 431), general information such as financial logistics and how to work with a musician in rehearsal, and a soon-to-come section on licensing musical recordings.

When Katz sees a gap, he fills it. In addition to offering educational resources and commissioning new works, Periapsis hosts an Open Series, which appeared in last month’s Brooklyn Bridge Arts Festival. As the Series curator, Katz seeks choreographers who work with composers and/or live musicians and offers them a paid performance opportunity. Last year’s open application process yielded five programs featuring 20 collaborative works.

For choreographers interested in working with live music, Katz offers this advice: understand that the performance of a piece of music is integral to the work itself. Envisioning an entire orchestra but can’t afford one? Katz suggests “broadening your musical horizons” and working with a paired down version that can be played live by just a few musicians.

In astronomy, periapsis refers to the closest point between two orbiting bodies. With his company, Katz hopes to align the stars and bring two disparate worlds close enough to share resources and knowledge, to help the other grow and flourish.

Periapsis Music and Dance will perform its June 2017 Season at GK Arts Center in Brooklyn, June 3-4. For tickets and more information, visit periapsismusicanddance.org/calendar.

By Kathleen Wessel of Dance Informa.