Becoming a respected, well-known and financially stable choreographer is no kind of easy path. The immense challenges along the way are numerous — financial capital, finding community, refining one’s authentic creative voice and simply materials such as quality footage of your work and suitable rehearsal space. Without emerging choreographers supported, considering these challenges, can “emerged” or “developed” choreographers ever come to be? What does dance as an art form look like if not? For those who love and appreciate all that dance art is, that’s a concerning question.

Thankfully, certain dance artists and enthusiasts recognize what’s at stake here, and have thus developed programs to address — in concrete, actionable ways — the obstacles that up-and-coming choreographers face. Dance Informa has taken a closer look at these specific challenges and how a particular program has worked to address the issue, speaking with the directors of those programs. These initiatives all have slightly different approaches toward the overarching goal of nurturing emerging choreographers, yet all have an important ingredient in common — all build community around the work of these up-and-comers. After all, just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to grow an artist.

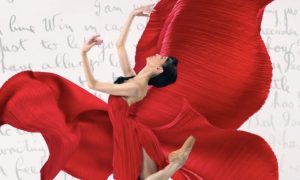

#1. Quality application materials to much more: Young Choreographer’s Festival

As a 19-year-old dance artist, Emily Bufferd was noticing something that distressed her; it seemed that presenters, curators, grant reviewers and other adjudicators were turning down younger, less established choreographers, not because of any lacking quality in their work, but because they didn’t have quality footage of it (professionally lit, costumed and sound-designed, rather than in a casual rehearsal setting). High-quality promotional photos seemed to be a similar barrier. Rather than just bemoan this state of things, she took action to do something about it. A chance to present work on stage could allow for several such up-and-coming dancemakers to obtain high-quality, professional photo and video of their work.

Thus, the Young Choreographer’s Festival (YCF) was born. Prospective participants apply online, and a panel selects those who will present work at the festival. Bufferd, YCF director and founder, expresses her belief in the importance of all choreographers having their work evaluated for key opportunities on a “level-playing field.” Thus, “YCF submissions only take into account the quality of the choreographic content, and not the quality of the actual video itself,” she explains. The mission of the festival has evolved to include educational initiatives for selected participants and the larger community, such as through a mentorship program (with a minimum of eight points of contact between a festival participant and a choreographic mentor). Going forward, Bufferd hopes to grow these educational programming initiatives. She also hopes to have a multi-night run at a renowned theater such as The Joyce.

Impressively, while working toward its 11th annual festival, YCF has presented over 150 choreographers. Bufferd believes that seeing these artists working in the field years later is “proof of concept”. As even more concrete evidence of mission fulfilled, YCF participants “have gone on to choreograph for television, film, Broadway, recording artists, internationally renowned concert companies and win some very prestigious awards for doing so (Princess Grace, Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, Lucille Lortel Awards and more),” Bufferd shares.

More specifically, the festival is in concert format (to provide that opportunity for high-quality video and photos of participants’ choreographic work). The night before the final showing, there’s a talk-back with a panel of industry professionals. Bufferd describes these panel discussions as extremely engaging. “YCF serves as not only an educational program and presentation for many of these young artists but also as a career building platform, where we promote them and help many of them get their name out there to be seen,” she asserts. “YCF has been possible because people in dance are generous and want to see others succeed, and I hope for YCF to continue on that trajectory of helping as many as we can.”

#2. Rehearsal space and feedback: Mark Morris Dance Center’s SharedSpace

Administrators at Mark Morris Dance Center noticed that there wasn’t a lot of crossover between professional dancers who took class and those who used rehearsal space, and they wanted to do something about that. They also saw how subsidized rehearsal space often came from having an upcoming performance, locking those who didn’t out of this essential ingredient of making work (considering the financial challenges of being an emerging choreographer). They devised a program to address both of those matters — SharedSpace, a season of performance opportunities with participants also eligible for low-cost rehearsal space at Mark Morris Dance Center.

Jessica Pearson, manager of adult programs at Mark Morris Dance Center, describes how another significant important benefit is at hand here — the opportunity to receive feedback on one’s work. She underscores how performance opportunities can be “costly, competitive and only focus on one genre of dance.” This can be problematic because feedback coming from such opportunities is “an essential part of the choreographic process,” Pearson asserts, with feedback from those outside of one’s “direct network” even more valuable. SharedSpace audiences are mostly non-dancers and unfamiliar with concert dance conventions.

These audience members “come from different backgrounds and experiences and can watch choreographers’ work without knowledge of their thoughts, process or patterns,” Pearson explains. They’re often hesitant to give feedback, but a welcoming atmosphere and feedback from others like them in attendance opens them up to sharing their experience of the work at hand before too long, Pearson shares. “This experience is different from a room full of dancers talking about dance. Time after time, choreographers express this unique environment being especially beneficial,” she adds.

Pearson explains how prospective participants submit an application to describe their work and why they’re seeking feedback, without video. They can apply for one or more dates in the SharedSpace showings season here. Five choreographers are selected by lottery for each SharedSpace event. Mark Morris Dance Center hires a different facilitator for each showing. This person “guides the discussion by setting parameters for the conversation, as well as posing questions to the group and sharing their own feedback” and is “responsible for engaging everyone, including practicing artists and audience members completely new to dance,” Pearson explains. This facilitator meets program participants the day of the event, when all involved have access to rehearsal space.

Pearson characterizes these showings as stylistically diverse, with many different dance styles represented. She also describes the use of live music in these events, which stems from the Dance Center’s value of live music as essential to dance.

With opportunities for emerging choreographers and for members of the general public to engage more closely with dance art, the program also aligns with Mark Morris’ belief that “dance is for anybody”. She also notes how many participants apply for the program subsequent times, to get feedback on the same work as it evolves or a new work, because they found the experience so valuable. Going forward, she hopes to see the program flourish and expand (such as in offering a performance and feedback outlet for teen choreographers).

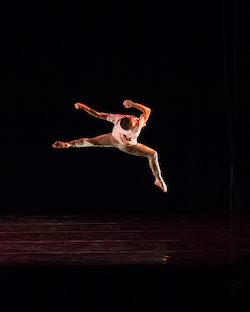

#3. Seeing one’s work and getting it seen onstage: Dixon Place’s Under Exposed

When NYC-based dance curator and enthusiast Doug Post took the reins of Dixon Place’s Under Exposed program, it was a bit of a pleasant surprise for him to be offered the role. He was a subscriber and frequent audience member of the venue’s season. As Curator, he sees a good deal of work in the city, he attests and notes choreographers whose work strikes him, moves him, makes him think. If such an artist fits into the Under Exposed’s mission of “focusing on emerging, up-and-coming contemporary dance choreographers who are refining/defining their distinctive styles,” Post will invite them to perform. He explains that most of these artists are based in NYC, but occasionally he’ll invite an artist from another region or even another country. Others apply online.

“We’re trying to provide exposure for people just starting out their choreographic career — in a first, second, or third year — and those who’ve, for whatever reason, had trouble breaking into other venues,” Post shares. “There are always newer artists who can use the exposure, there’s never a shortage of people to present in the program,” he adds. Exposure to presenters, curators, and the like, as well as the general public, is one important advantage here. Yet it’s also key in a choreographer’s journey to see their work on stage, with full production values. “There’s only so much you can do in a studio — seeing something you’ve made presented on stage is a whole other story,” Post affirms.

Another part of getting a work on stage is the opportunity to have it reviewed. Post says that a reviewer coming to one of these showings is not all that common, and he doesn’t invite them. Occasionally, a presenting artist will be able to get a reviewer to come, and in those cases, Post polls those presenting if it’s acceptable for a reviewer to come; works presented in the series are often works-in-progress, so some artists would rather not have a reviewer see them at that stage of creation.

In terms of practicalities, it can be a bit of a logistical shuffle to fit invited choreographers into nights in the program’s season when they’re available. Post shares that he doesn’t curate works to a specific theme, given those challenges with availability. Sometimes works in a night of the program fit together well as a theme, and in others they’re “all over the map,” he says — which can be intriguing and striking in its own way. Post has some themed-curation ideas for upcoming seasons, however, such as spotlighting African American choreographers for Black History Month and a retrospective of the program in 2021, the 10th anniversary year of Post curating Under Exposed.

At the question of what may happen for artists after presenting work in the Under Exposed series, Post asserts that there’s nothing transactional at hand here, yet that exciting things do happen for some who’ve done so. “You never know when a spark can be struck and things can just take off for an artist,” he affirms.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.