David H. Koch Theater, New York, NY.

November 7, 2019.

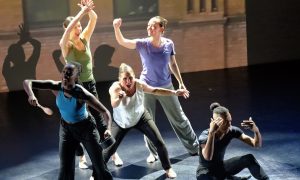

As humans evolved, they moved together to praise spirits — those that brought health and sickness, plenty or scarcity, weather good or disastrous. Short of how formalized religion also evolved as history trotted on, we continued to move to express, protest, show gratitude and more. We found, consciously or consciously, the power of movement to express our spirituality — the very spirit lying within our bones, muscles and sinew. Watching Paul Taylor American Modern Dance’s program at Lincoln Center, I thought about this spirituality within movement; there was something transcendent and even divine in how the company moved, together and apart. Some works told a more direct human narrative than others, yet all works reflected our ability to rise above, reach higher and move toward harmony.

The program opened with Paul Taylor’s Airs, a work that left me feeling peaceful and soothed. A tranquil feeling was present from the very start. Blues in lighting (by Jennifer Tipton) and costuming (by Gene Moore) made me breathe more easily. Formations were geometric and even. Movement of classical lines yet a smooth release brought aesthetic harmony. The score, works from Handel, offered a calm, yet nuanced and intriguing auditory frame for these elements. A motif of arms reaching up in a “V” shape created a sense of reaching up to the heavens, as well as mirroring curvilinear shapes in nature. This shape came in virtuosic jumps. leaps and footwork — bringing forward fresh movement possibilities in combination with a calming, grounding element.

Dancers dipped their torsos to the side and stacked their spine to another side of the stage after turning. They repeated this movement vocabulary to a new facing, adding new nuances, reinforcing that quality of the familiar with the fresh and new sprinkled in. Virtuosic movement had a softness that made these seemingly superhuman technicians in front of us on stage feel more human. Although the work was largely non-narrative, little theatrical and humorous moments further humanized the dancers. It all felt digestible and accessible, even with movement bringing complexity that reflected the multifaceted nature of the human spirit.

Also multifaceted, yet accessible was how movement related to the music — sometimes in accordance, sometimes in opposition. A memorable example of the latter was dancers tripletting (a pattern of three steps, changing levels and rhythms) double the speed of the music accompanying the movement, while at other times, they moved at the music’s same speed. These variances in the relationship of music and movement throughout the work established a challenging musicality, but the dancers executed it without any noticeable flaws. To end, the dancers joined in a clumped formation at center stage, gazing forward with a clarity of conviction and fearlessness. They seemed to assert a strength lying in their unity — strong alone, but far stronger harmoniously together.

The second work, Margie Gilis’s Rewilding (2019), brought a notable shift in mood, atmosphere and aesthetic. Dancers entered and walked slowly in lines, bringing a sense of sameness and routinization. Lighting in earth tones was low (also by Tipton). Costumes were in different colors for different dancers, but all also in earth tones (by Santo Loquasto). Deep tones in the music, in combination with this routinized movement, created a somber mood. One by one, dancers began moving in their own way, breaking out of that rather ordered unison movement — until they were all dancing their own movement vocabulary. This movement had a conviction, but a lightness and ease not seen in group movement.

I wondered about the balance of moving together, but as individuals. As is all too common in this world, this group wasn’t finding that. The group recohered into a circular path, recreating a sense of sameness and monotony. It was as if these individuals sought to find originality but were somehow compelled back to act along with the group. Coming back to movement motifs from earlier in the work, as well as repetitions of such dissolving and recohering, reinforced that theme of being compelled back to the action and modes of the group. Solos and duets brought us further into individual experience, in contrast to group section. Leaps locomoting across the stage evinced freedom and possibility. Soon, in a group section, the dancers shook as if in extreme agitation, another stark contrast. Clearly enough, group conformity didn’t bring joy and ease.

To end, most in the group settled in a formation, yet one dancer walked off. I thought about individual and group consciousness, and the tension that can emerge between those two things. “We need not abandon technology but rather weave it with experiential wisdom. Rewilding the way we live,” the program notes asserted. We musn’t abandon the connections that technology offers but also return to our own inner wisdom was the message that I found within the work that resonated with me. It seemed to me that this message spoke to human spirituality, which the work adeptly expressed in movement and design.

Black Tuesday closed the program, choreographed by Taylor and first performed in 2019. The title refers to the day in 1929, when the stock market crashed so significantly that it began the Great Depression of the 1930s. This specificity would continue through the work, atmospherically and in theatricality of movement. There was also universality to it, however, speaking timelessly to aspects of the human condition — a spirituality of its own. A city skyline filled the backdrop as the work began, lighting low to help build the atmosphere of urban nightlife (set designed by Loquasto). A group moved together, dressed in 1920s clothing — simple yet detailed enough to help bring us into a 1920s world (costumes also designed by Loquasto). Classic jazz music further shaped and colored this world. I was in it.

There, the dancers moved in those groups with formal clarity but also with the sense of ease and fun found in old-time jazz clubs. Gestures built a sense of playfulness. In typical Taylor movement idiom fashion, classical lines and sprinkles of virtuosity were softened and eased to feel more grounded and human. It all felt pleasantly authentic. Duets and solos coming soon focused us from collective experience to that of individuals. Larger groups, and a group of duets, brought us back to collective experience — yet with that more individual experience still in my mind’s eye. The classic jazz club atmosphere remained.

Formations, and shifts to new formations, also took on additional complexity. A thoughtfulness and intentionality of image kept it all digestible and satisfying. For instance, a circle opened up to a large pyramid. The arch of flight in lifts reflected a shooting star, connecting with the stars that came to fill the backdrop — one depicting a night sky. I thought about those classic synchronized swimming videos, large groups in moving formations that created complex images, those that somehow still stayed clear and impressive. In another reference to an alternate movement style, a kickline reflected precision dance. A memorable solo toward the end conveyed the pathos of living within the economic distress of the 1920s, yet without being overwrought.

The soloist moved powerfully through different levels and places on stage, gesturing with conviction and authentic emotion, while music accompanying him pronounced “brother, can you spare a dime?” The song poetically told a heartbreaking riches-to-rags story, the kind that do keep recurring in this world — adding an element of timelessness to the stage action. Unique and pleasing movement, intriguing concepts, adept design — the program offered it all to demonstrate the spirituality, the divine nature even, in the human body’s movement. As of late August 2018, Paul Taylor has no longer been with us. Yet it seems that the company he founded, under new Artistic Director Michael Novak, will continue to carry forth his legacy and mission — as he smiles down pleased and proud.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.