In New York’s premiere dance studios, you’ve got to have both a stellar resume and a codified class in order to score an official slot of the sought-after Advanced Theatre classes. Those weekly professional classes are a legacy all their own, as over the years class slots have been held by the likes of Chris Chadman, Chet Walker, David Marquez, Randy Skinner, Andy Blankenbuehler, Josh Bergasse, Al Blackstone, and now: James Kinney.

You don’t even have to be a dancer in Kinney’s class to experience the electrifying energy that emanates from his studio. Peering through the foggy window, you realize the complete equation of what makes a great class: 1) choreography that is informed and innovative, 2) music that feeds your soul, and 3) dancers who leave class sweaty and smiling.

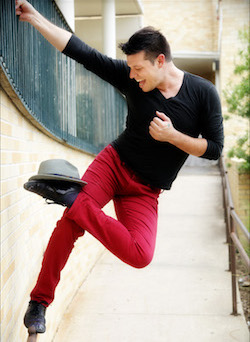

James Kinney. Photo courtesy of Kinney.

Kinney’s movement is both like and unlike anything else you’ve seen. You notice influence of the “greats”: Robbins, Fosse, Cole, Bennet, Hatchett and even Graham. Nevertheless, everything is fresh and new and stylized — a technique all its own.

Dance Informa was able to sit down with Kinney after one of his packed classes to learn how his training, mentors, performance experience, inspirations and boldness have all helped to cultivate his signature style — one that dancers are hungry to perform and audiences have been waiting to see.

Where did you grow up, and when did you begin dancing?

“I grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. From an early age, I wanted to become an opera singer like my mother. But when I was about 11 years old, I watched Michael Jackson perform ‘Beat It’ on TV and immediately became interested in dance. My mom signed me up for ballet class, but I quit right away because I hated being the only boy amongst a sea of pink tutus. It wasn’t until I trained at Janet Syndor’s dance studio that I felt more comfortable. She didn’t put a spotlight on me or give me special attention because I was a male dancer. She just let me dance. And then Frank Hatchett came to teach a master class at Janet’s studio, and I was blown away. I had officially caught the dancing bug!

As I grew older, I tried to learn and experience everything I could. I attended the Douglas Anderson School of the Arts, where I took classes in music, acting, voice and dance. After school, I would take company class as an apprentice with the Florida Ballet Theatre. And at night, I performed in productions at the Alhambra Dinner Theatre, the oldest dinner theatre in the country. Then one year, Ann Reinking came to town to audition kids for the Musical Theatre Project in Tampa (now the Broadway Theatre Project). I was one of maybe four kids from my town to get accepted in this incredible three-week intensive with teachers like Stanley Donen, Gregory Hines, Jule Styne, Dudley Moore and Chet Walker, who would become a huge mentor for me. At the Musical Theatre Project, I learned repertory from all the great choreographers — Jerome Robbins, Jack Cole, Matt Maddox and Bob Fosse. That was certainly a turning point for me.”

What launched your career?

I moved to New York City at just 20 years old. I was overwhelmed by the city but found comfort and confidence in dance classes where I could continue to learn, train and develop my craft. One of my first big gigs was the European tour of West Side Story. Robbins’ choreography taught me two lessons: 1) Dance is so much more than just steps, and 2) As a dancer, your job is to perform the choreography exactly as the choreographer asks — without any embellishments or ‘-isms’.

I was later cast in another dream show, as the male swing in the national tour of Fosse. After many months with the touring company, I was itching to make my Broadway debut in the show. But I was never called in to audition because, as a swing, I was too vital to the touring company and, frankly, too expensive to replace. So, I took a big risk. I quit the tour and moved back to New York City. That same week, I was called in to audition for Fosse on Broadway, and I finally booked my Broadway debut!”

How did you make the transition from dancer to teacher?

James Kinney (center). Photo courtesy of Kinney.

“It was Chet Walker who really encouraged, or rather, kind of forced me to become a teacher. I was performing for a week at Jacob’s Pillow, and Chet insisted that I teach a class to his students…but I didn’t know how. He put me in the studio with a drummer, 16 dancers and said, ‘Go!’

In my initial classes, I would borrow all my favorite warm-ups and sequences from various teachers and mentors. It was most definitely a learning experience for me. As I grew more assured, I began creating choreography fully founded on the technique I had learned, but I gave myself permission to move like me — with all my own quirks, tendencies and ‘-isms’.”

How has your experience as a dance captain for shows like Fosse and Sweet Charity influenced who you are as a teacher and choreographer?

“Being a dance captain taught me how to teach. When new dancers were put into the show, I had to teach them their ‘tracks’. To get a dancer to execute exact choreography, you might have to use different techniques such as technical terminology, demonstration or imagery to make sure they execute it exactly as the choreographer intended. As a dance captain, you’re really in charge of keeping the show true to itself.”

What inspires you?

“I’ve certainly been inspired by the great teachers, mentors and choreographers for whom I’ve danced over the years. I’m also inspired by art, specifically the interesting body shapes in the Art Deco paintings of Erté. And I’m so inspired by music, too. My mom was an opera and jazz singer, and I love the freedom, drama and style of jazz music.”

Your choreography is both technically challenging but also musically intricate. You often speak in rhythms instead of counts, isolate movements on quarter or even eighth notes, and talk about pushing the beat or sitting into a pocket of music. Can you speak to this a little bit?

“Like I said, I’m so inspired by music, especially jazz. I like to challenge dancers to use both their body and their brain in class. I love the idea that dance is music made visual. I should be able to ‘hear’ the music just by watching you move.”

‘Style’ is a term that is tossed around a lot in the dance world today. How do you define style’?

“Style is an attitude, a frame of mind. I feel that a person has style when he accumulates and truly owns his ‘-isms’. Then it sort of becomes a new vocabulary all its own.”

It’s clear that you’re inspired by the greats — Bob Fosse, Jerome Robbins, Michael Bennett, Frank Hatchett, Matt Maddox and Jack Cole. Still, your choreography is quintessentially yours. You don’t use their steps or style verbatim but rather create movement that is both informed and still wholly innovative. How are you able to do this (and so effortlessly)?

James Kinney’s musical theatre class. Photo courtesy of Kinney.

“I invite [them] into the room, but at a certain point, I tell them to be quiet! I consider all the technique and style and choreography I’ve learned over the years, but then I let my ‘-isms’ take control. I let the movement settle into my bones; it has to feel good to me. The greatest joy is when I watch my choreography and think, ‘Now that’s James.'”

What are your career goals?

“I want to keep working as much as I can in theatre, film and TV — not only choreographing but directing, too. I dream of one day collaborating on an entirely original work. I’m also itching to perform again…once a dancer, always a dancer!”

To learn more, visit www.jamesakinney.com.

By Mary Callahan of Dance Informa.