That first day, he wore the brightest smile, instantly creating a warm and almost comforting atmosphere for our group of 14 female dancers from around the globe. He described every movement with such care, like each step was a line out a movie that held such tremendous purpose to the plot. If anything was out of place, it would ruin the story. Everything was connected and flowed like lyrics from the most beautiful song. I knew then that he was teaching us how to dance.

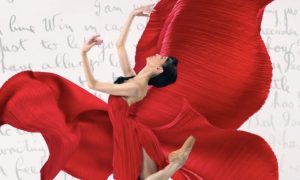

Ricardo Amarante’s ‘In Flanders Fields’. Photo by Johan Persson.

I first took class from dancer-choreographer Ricardo Amarante at the Adeline Genée International Ballet Competition in Antwerp, Belgium, in 2014, and I was immediately inspired by his dynamic neo-classical style and incredible passion for the arts. I marveled at his deep sense of musicality and intricate attention to artistic nuances. He coached every candidate with the intention of bringing out their personal best. Along with some required soul-searching from each dancer, Amarante wished that every individual evolve him/herself while enjoying the process of learning his work.

With this passion and dedication to dancers, it’s no wonder then that Amarante has made quite the career as a dancer, choreographer and educator. Originally from Brazil, he was a semi-finalist of the Genée in 1998 after training at the National Ballet School of Cuba on scholarship. At the conclusion of the competition, he was offered another scholarship to the English National Ballet School, where he earned the prestigious Royal Academy of Dance Solo Seal Award. Amarante went on to dance and tour professionally with the Paris Opera Ballet and Jeune Ballet de France. Currently, he resides in Antwerp, where he performs as a soloist with the Royal Ballet of Flanders and also continues his 10 years of choreographic works with the company.

Ricardo Amarante’s ‘In Flanders Fields’. Photo by Johan Persson.

“I love working with dancers, coaching and making them improve,” says Amarante, when I ask him about his decision to take on the life of a choreographer.

Recently, Amarante has been hard at work producing multiple projects with the Royal Ballet of Flanders, including Quatro por Quatro and In Flanders Fields. Both of these distinguishing works were performed at the Flemish Opera House, the company’s main stage, as well as other venues. When asked how these ballets came about, the choreographer/dancer notes that both projects emerged from contrasting avenues.

Amarante says that Quatro por Quatro evolved from “four movements, four composers, four ballerinas, four different feelings”. To create this unique ballet, he first found his four special dancers, then four different pieces of music by different musicians to match the style and quality of each dancer. In Flanders Fields, however, came to be through a much different approach. It began with a theme, World War I, and then Amarante created the whole story and searched for a composer to produce the music.

Ricardo Amarante’s ‘In Flanders Fields’. Photo by Johan Persson.

While some artists may be unhappy with many of their masterpieces, Amarante is torn when trying to pick a favorite work. Each ballet to him is like a son, and he says, “Can you pick a favorite son?!” He adores every piece that hits the stage, and reviews are reciprocating his overflowing excitement. The Dancing Times declared In Flanders Fields to be full of “impassioned choreography, emotional intensity and masterful commissioned music”.

He has been fortunate enough to work with composer Sayo Kosugi, who assisted in the creation of In Flanders Fields, one of his favorite ballets. I had the honor of being exposed to Kosugi’s music as well, as she assisted in the composition of the music for the Genée’s commissioned variations. With an enticing underlying darkness and powerful quick upbeats, Kosugi’s music perfectly matched the strong and fierce dynamic movements required by the female candidate piece.

Ricardo Amarante’s ‘In Flanders Fields’. Photo by Johan Persson.

In comparison with his different works, Amarante admits this process resembles having two sons — one being the ballet and the other the music — and that every opportunity to create is a very special and emotional journey. As a passionate artist, he has been influenced by many and will continue to impact people again and again with his powerful and emotionally riveting works.

For Amarante, the most rewarding part of choreographing is “seeing the development and improvement of a dancer and to see them enjoying performing my ballet,” he shares.

To all dancers who wish to pursue a path of choreographing, Amarante advises, “You have to love it and have a lot of passion for it, to be patient and not be afraid to try new ways.”

By Tessa Castellano of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): Ricardo Amarante’s, ‘In Flanders Fields’. Photo by Johan Persson.