Le Spectre de la Rose, Les Sylphides, Petrushka, The Firebird. These ballets would not exist without Michel Fokine’s artistic genius. Fokine’s ballets have lived on through the years and now, in the 21st century, his direct descendants carry on his legacy.

Nicholas Fokine, great-grandson to Michel, studied at School of American Ballet and has performed with New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, Miami City Ballet and Carolina Ballet. He currently serves as Superintendent of Operations for the School of the Carolina Ballet. His aunt, Isabelle Fokine, is the artistic director of the Fokine Estate-Archive with Nicholas serving as assistant répétiteur and coach. He took time out of his busy schedule to speak with Dance Informa.

When you were growing up, were you aware you came from a legendary family?

“Understanding the full scope of his achievements was an incremental journey for me. Before I began studying ballet, I had seen his (Michel Fokine) works performed both live and on video. Our apartment was filled with large posters from productions featuring my great-grandparents, along with paintings by Michel himself. I knew this wasn’t ‘typical,’ but it wasn’t until I began my ballet training and meeting members of the dance community that I grasped the full significance of the Fokine name.”

Can you give us a sense of the scope of the Fokine archives — what kinds of materials are preserved?

“The archives are comprised of hundreds of items including his memoirs, diaries, paintings, sculpture, set and costume designs, sketches, costumes, audio recordings, artifacts, posters, photographs, scores, orchestrations, dance-notations, rare books, manuscripts, press clippings, programs, contracts, correspondence, personal mementoes, archival film footage, etc.”

Fokine revolutionized ballet in his time. How do you see his ideas resonating in the ballet world today?

“Fokine’s revolutionary influence runs through nearly every dramatic ballet created in the past hundred years. It often goes unnoticed, not because it’s absent, but because it has become so deeply embedded in the art form. Anytime a ballet conveys a narrative through expressive movement instead of traditional mime, when the costumes and sets reflect the period and characters with authenticity, or when all artistic elements are woven together to form a cohesive vision, his legacy is at work.”

Are there any common misconceptions about his work or philosophy that you would like to correct?

“With regard to the impact of Fokine’s individual ballets, something very odd has happened. Because they are seen as ‘old’ and therefore historical, they are often presented in a way which is in complete contradiction to Fokine’s original intentions.

Les Sylphides is a perfect example of this. It is typically approached incorrectly in one of two ways. As a classical ballet with academic port de bras and slow tempo, or as a romantic ballet in the same vein as Giselle, somber and with downcast eyes. It is neither! This ballet aimed to revive the spirit of the Romantic era, reinterpreted through Fokine’s reforms. The piece evokes a joyous atmosphere, in which sylphs are gliding through the moonlit forest while a poet is swept away by his visions of them.

Fokine’s works, when performed authentically, still feel remarkably contemporary. The Fokine work I’ve seen performed most often in my lifetime is The Dying Swan, which is frequently treated as if it is an excerpt from Swan Lake. That is exactly what Fokine was revolutionizing ballet to move away from. When danced as Fokine originally intended, it becomes a far more nuanced, dynamic, musical and expressive work, one that breaks significantly from the classical balletic mold. All this to say, it is very important to remember the context in which these works were created.”

Have you been involved in recent re-stagings or reconstructions? If so, what’s that process like?

“I was just at Birmingham Royal Ballet, in April, coaching their second company on a number of works including Les Sylphides, Spectre de la Rose, The Firebird and Scheherazade. I find the process to be incredibly gratifying. Dancers of today do not receive acting classes as a part of their training, and their approach tends to be focused on the external, rather than creating a movement as the physical extension of an internal thought. The highlight when teaching Fokine’s works is seeing the lightbulb turn on when you explain to a dancer why they are doing an action and watching that translate into how they perform the step or gesture. Giving them permission to explore the internal dialogue and how that permeates into the movement. It’s as if the ballet suddenly makes sense. Nothing in Fokine’s ballets is arbitrary or superfluous; there is purpose to be found in every moment.

Part of why I find this particularly satisfying to bring this out in others is from personal experience. I recall as a teenager working with my aunt in the studio, learning the ballets. Her explaining what was happening in a sequence of steps and me feeling those moments of connection between thought and movement and saying to myself, ‘That felt good!’ This approach made my dancing feel sincere and gave me a sense of freedom to not solely fixate on the physical nature of dancing but to incorporate the feeling element. This newfound artistic sensibility was transformative for me as a dancer and performer.”

Are there any upcoming projects, restorations or collaborations involving the estate that you’re excited about?

“There are a number of projects in the works. Here are ones at the top of the list:

I am working on a new edition of Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master. Originally published in 1961, this book was compiled by my grandfather, Vitale, who assembled the memoirs and writings of his father, Michel Fokine. He filled in gaps where necessary to create a cohesive narrative of Fokine’s life in his own words. The original book was heavily edited. I am assembling a new, unabridged edition that will be released as an e-book including additional chapters, photographs, archival video footage and more.

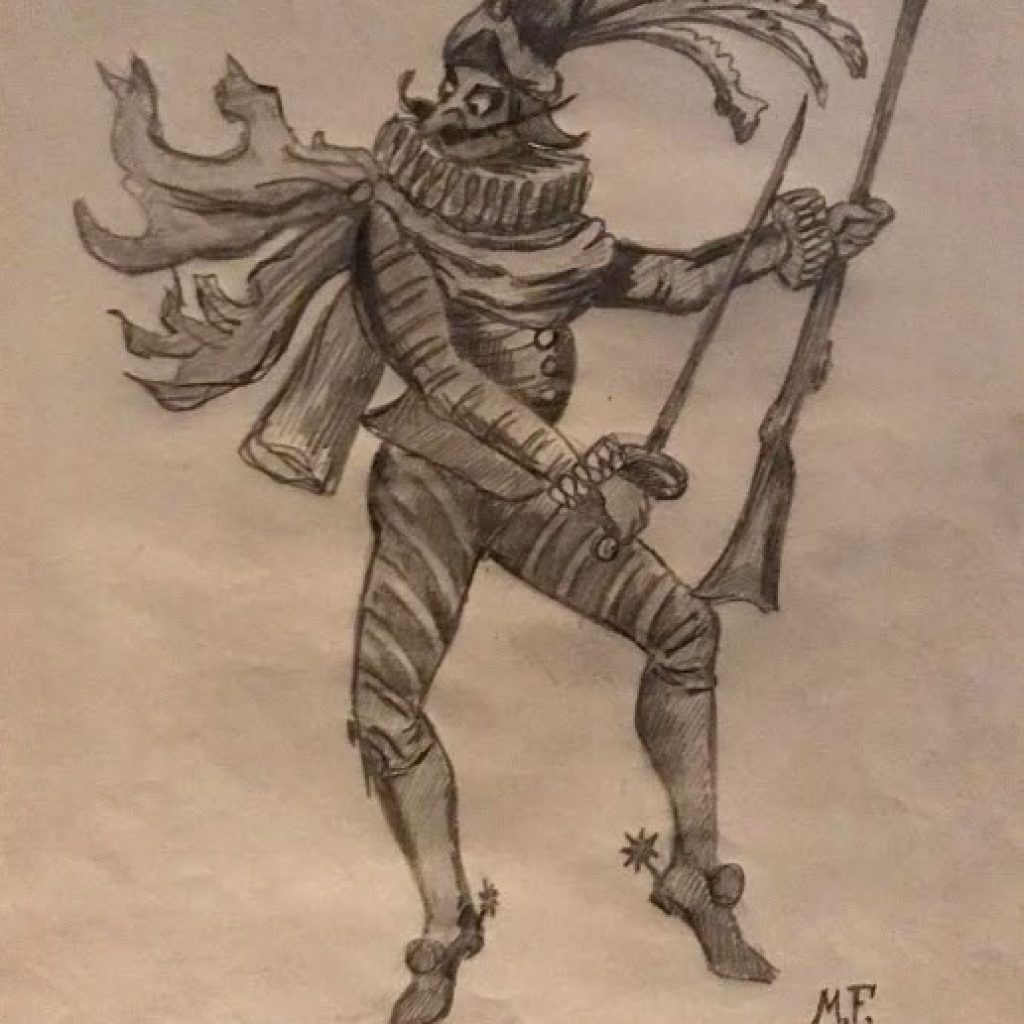

The estate is also in the planning stages of a revised production of Petrouchka. With small but essential revisions to replace the out of date and inappropriate Moor puppet, a product of Benois original designs, with a Russian Cossack warrior. This change would focus on the set for the Moor’s cell, his costume and his coconut (to be replaced with a Slavic Easter egg). These changes will not impact the integrity of the choreography but will make the ballet compatible with modern sensibilities.”

What hopes do you have for how future generations will engage with Fokine’s work?

“I hope that future generations approach Fokine’s ballets with an understanding of his original intentions, as this is key to preserving their artistic and historical integrity. His works should not be seen merely as museum pieces, but as living, breathing art that was revolutionary in its time and remains deeply relevant today. I hope they continue to be recognized not just for their beauty, but for their bold departure from tradition, ushering in a new era of expressive, narrative-driven ballet. Fokine’s choreography represents a pivotal turning point in the ballet canon, and I believe that, when faithfully interpreted, his ballets still have powerful stories to tell and emotions to evoke.

For more on the Fokine Estate, visit www.michelfokine.com, or you can follow the Fokine Estate-Archive on Instagram: @fokineestatearchive.

By Mary Carpenter of Dance Informa.