The simplest definition of an artist may be one who shapes a certain material – be it clay, paint, music or the human body. Yet what might we call artists who shape the nature of the art of their time itself? Broadly speaking, artists most often follow the general artistic trends of their generation, and what the surrounding society will recognize enough to support. Some artists, however, put forth the cunning and courage to alter the direction of the art of their time – and thus also change its future course.

Trisha Brown. Photo by Lois Greenfield.

Trisha Brown, who passed away on March 18, was one such artist. She had been in treatment for vascular dementia since 2011. She obtained her undergraduate degree in dance at Mills College in 1958. Key influences at this early stage of her career were Simone Forti and Anna Halprin, from whom she learned methods for forming improvisation into a (somewhat) repeatable performance. These include “task-based improvisation” (movement driven by the process of accomplishing a certain task) and “rule games” (seeing what might transpire from having one to a few rules shape one’s movement). She transplanted to New York City in 1961. The following year, she helped found Judson Dance Theater with fellow post-modern dance pioneers such as Steve Paxton and Yvonne Rainer.

Like dances of those colleagues, her works “eliminated bravura, academic technique, acting and musicality” – fundamentals of concert dance (both ballet and modern dance), explains Alastair Macaulay, chief dance critic for The New York Times.

In her treatise on “Pure Movement”, Brown stated that she does not “promote the next movement with a preceding transition and therefore, I do not build up to something.” This is an unapologetic departure from the convention of building dramatic arc, whether in overarching narrative or in the body, that is so key to plot or theme-based dance. For Brown, and for post-modern dancers of decades after, the possibilities of the body can provide drama or “message” enough. “Pure movement is movement that has no other connotations,” she asserted.

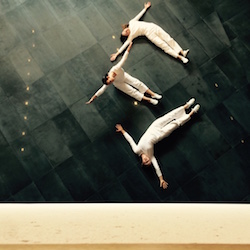

TBDC in ‘L’amour au théâtre’. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Brown’s early works also revealed her penchant for seeing, and subsequently engaging with, spaces in wholly original ways. In 1970’s Walking on the Wall, for instance, dancers walked on walls, and audience positioning granted the optical illusion of looking down on the performers from above. Wendy Perron, Dance Magazine editor-in-chief and former dancer for Brown, recounts how “[Brown] said she felt sorry for places that weren’t center stage – the corners, the walls and wing space….she caused a revolution by simply, sweetly turning to spaces that other dance-makers don’t.”

And post-modern dancers have danced in unexpected spaces ever since – in trees, in swimming pools, nearly anywhere that will hold bodies moving in time. Brown also engaged with the space of the body in a revolutionary way. She had no qualms with seeing audiences in a yet-unseen way as well; she stated in her treatise that she “may perform an everyday gesture so that the audience does not know whether I have stopped dancing or not.” She was in no way beholden to the presumed tastes or understandings of her audience members. “I…use quirky, personal gesture, things that have specific meaning to me but probably appear abstract to others,” she explained. No more to it than that.

Trisha Brown. Photo by Marc Ginot.

Despite this attitude to audience mentality, Brown’s approaches began to gain recognition and admiration, in earnest, with 1983’s Set and Reset. She gained a following in France in particular, and in 1988 the French government named her Chevalier dans L’Ordre des Arts et Lettres – a unique honor granted to artists, writers and the like who are highly admired in France.

In later years, Brown returned to the proscenium stage. She also more frequently used a method called accumulation, a repeated movement then layered on with another movement, and so on to build phrases. This was in line with her tendency to challenge audience members, claims Joan Acocella in The New Yorker, to “deflect their focus”. Brown asserted that when “moving to the right, I will stick something out to the left…to set up some sort of reverberation between the two.”

Brown also transitioned from using silence to classical music scores because she was tired of hearing the audience coughing, she claimed. Tongue-in-cheek, yes, but she could also roar like a lioness. When asked, earlier in her career, why she didn’t use music for her dances, for example, she responded, “Do you walk around a sculpture and ask why there is no music?”

TBDC at Museo Universidad Navarra in Pamplona. Photo by Alexandre Moyrand.

She was called generous and caring toward her dancers, and she clearly “invited people to think, move and see differently”, Perron asserts.

Brown describes herself best – perhaps accidentally – in her treatise, stating that she “[made] radical changes in a mundane way”. She was not the only seminal dancemaker of her generation, of her circle of post-modern dance pioneers, but she was uniquely influential. May dancers, choreographers and all who experience some part of her legacy come away thinking, moving and seeing – in some small way – differently, newly and daringly.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.