In some circles of contemporary choreographers, the word “formal” has a negative connotation. It implies an adherence to Westernized, balletic ideals like line, shape and symmetry. For those who want to set themselves apart from ballet, it can also call to mind an old-fashioned, rigid aesthetic. Especially in New York, where artists vie for attention in a crowded field, “conceptual” tends to be the more highly valued descriptor.

Lydia Johnson and Deborah Wingert coaching. Photo by Melissa Bartucci.

Not for Lydia Johnson, who bristles when I ask about the concepts behind her work. “My work is not conceptual,” says the New York choreographer, who founded her company Lydia Johnson Dance in 1999. “My desire to choreograph springs from the music,” she says. And just as great music doesn’t need a concept to be effective, neither, Johnson believes, does dance. “What is the meaning of a Bach piece?” she asks. Its beauty lies in its composition: carefully crafted melodies, rhythmic structure and instrumentation. Her advice to those seeking a meaning behind her work? “Let non-conceptual work wash over you like music,” she says.

Johnson started dancing in high school, (“very late,” she says) after years of watching figure skating on TV with her dad. “I grew up in the country in Massachusetts and didn’t know there was such thing as a choreographer,” she says. Right from the beginning, she was drawn to movement creation and was fascinated by the patterns, structure and clean lines she saw in skating and ballet. She trained in Boston and later the Ailey School in New York with the goal of gaining enough technical knowledge to begin making her own work. She went to concerts in New York but didn’t find real inspiration until she saw New York City Ballet. “The lines of ballet cause me to have a meltdown, they’re so beautiful,” she shares.

Kerry Shea and Carlos Lopez in Lydia Johnson’s ‘Night and Dreams’. Photo by Nir Arieli.

When she began choreographing, she knew she wanted to infuse ballet’s form with emotion and carefully crafted musicality. Well-known dance writer Jennifer Dunning once wrote that Johnson “reworks components of classical ballet technique to create a sense of life flowing unhurriedly over mysterious human stories.”

Johnson likes this description. She prefers to think of her works as “ballets” in the European sense, a looser term that doesn’t necessarily imply strict classical technique and pointe shoes. With weighted movement, floor work and contemporary partnering reminiscent of early American modern dance techniques, Johnson strives to create “emotionally evocative, abstract work”.

Videos of her work reflect a deep respect for the art of ballet, and recent staffing changes point to a new direction for the company: one that fosters a stronger connection with the classical tradition. To unify her dancer’s movement quality, Johnson hired ballet mistress Deborah Wingert, a former Balanchine dancer who also sets work for The Balanchine Trust, after Philip Gardner introduced them and they realized they were both deeply drawn to musically-motivated dance movement. In addition, guest artist Carlos Lopez, a former American Ballet Theater soloist, performed in the 2013 premiere of her work Night and Dreams.

Although Johnson continues to draw inspiration from music, she has begun to experiment with movement as a starting point. “I’m older now,” she says, “and my voice is stronger.” She says she’s often awakened late at night by images that “want to be developed”. She sees formations – like a group of bodies in a line or a cluster upstage left – first and then looks for the right music to “match” her ideas.

Chazz McBride and Min Kim in Lydia Johnson’s ‘Giving Way’. Photo by Nir Arieli.

This process of self-reflection and growth points to Johnson’s fundamental respect for the many years of training it takes to find one’s choreographic voice. She’s a big proponent of “paying your dues” as a dance-maker. “There’s a danger in trying to go too fast, throwing stuff out there before you’ve spent the hours in the studio really finding out who you are,” she says. And again she references music. “You would never accept a [composer] not knowing composition,” she adds.

To her credit, Johnson practices what she preaches. She founded a school in New Jersey with the intention of educating young people about dance through the practice of creating it. “Kids are way more motivated when they can create,” she says, referring to her unique approach that rejects the typical recital-based model. Students ages four through 18 learn technique in tandem with age-appropriate compositional concepts like levels, counterpoint, canon, and theme and variation. They learn that unison has to be used sparingly and decisively to make a powerful impact. Through classes, workshops and summer camps, students interact with Lydia Johnson Dance company members in an environment that supports collaboration and creativity. Each session ends with an informal showing of group works the kids have choreographed themselves.

With recent performances at the Ailey Citigroup Theater and a repertory workshop at the Peridance Capezio Center in New York, Lydia Johnson Dance has been busy. Johnson hopes, in a sea of concept-driven work, her staunch adherence to line, shape and structure stands out. “People tell me they didn’t know this kind of dance existed,” she says. “’It’s a fusion of emotion and form.”

By Kathleen Wessel of Dance Informa.

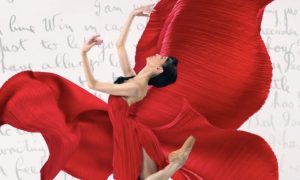

Photo (top): Brynt Beitman and Laura Di Orio in Lydia Johnson’s ‘Giving Way’. Photo by Nir Arieli.