June 1, 2019.

The David H. Koch Theater, New York, NY.

In his time, William Shakespeare was a maverick innovator; he literally created hundreds of words that we now regularly use in the English language. The same can be said of George Balanchine, who blended an American sensibility into the structure of classical Russian ballet. They could both be ironic, sarcastic and goofy, even while at other times being sanguine, formal and grandiose. Both also left an indelible creative legacy.

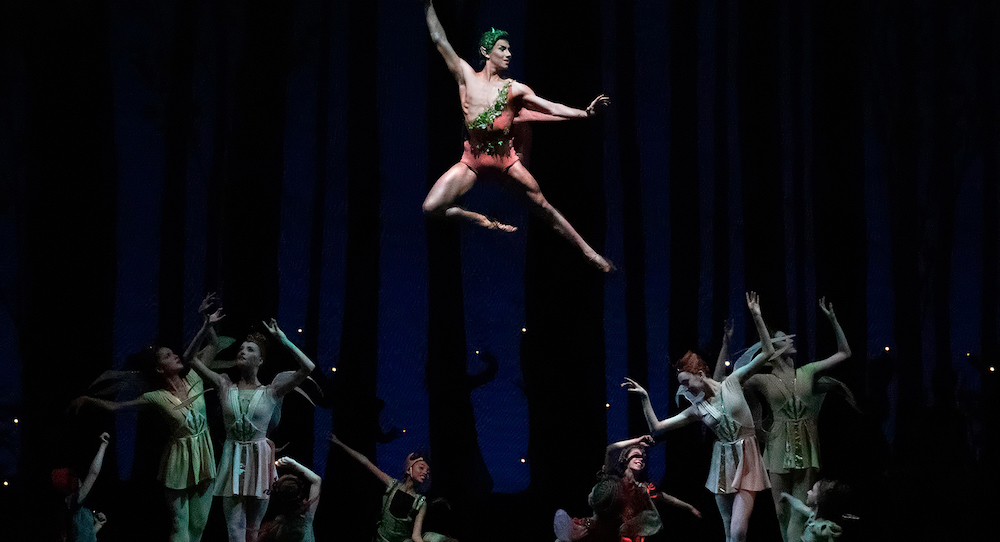

Daniel Ulbricht as Oberon in George Balanchine’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

At the intersection of these two artists are Shakespearan ballets such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The Balanchine Trust shares that “Shakespeare’s 1595 play has been the source for films, an opera by Benjamin Britten (1960) and a one-act ballet by Frederick Ashton, called The Dream (1964). George Balanchine’s version, which premiered in 1962, was the first wholly original evening-length ballet he choreographed in America. On April 24, 1964, A Midsummer Night’s Dream opened the New York City Ballet’s first repertory season at the New York State Theater.”

New York City Ballet (NYCB) presented the neoclassical work with joy, technical command and inventive touches. The program noted that “it is called a ‘Dream’ because of the unrealistic events that the characters experience in the play — real, yet unreal, such as crossed lovers, meaningless quarrels, forest chases leading to more confusion and magic spells.” One memorable touch of this fantastical magic, this magical realism, was a cupid’s arrow hitting a sizable heart shape at center stage, glowing red upon the arrow’s impact.

Overall, a first aspect that caught my eye, my brain and my heart were formations, particularly in connection with the movement occurring within them. Circles brought a feeling of softness, embodied in strong port de bras and tight turns. Likewise, shifts to “v”-shaped formations connected with shifts to more angular movement — “v” arms (low and high) and sharp petit allegro. Set design (by David Hays) and Costume design (by Karinska) next grabbed my attention, all in the bright pastels of summer’s vibrant plant life. Large hanging plants framed the stage, dangling before the cyc backdrop. Pastel-colored lighting (by Mark Stanley) filled this cyc, as well as bathed the stage. In all of this there was something of this world but also something magical beyond it.

Miriam Miller as Titiana in George Balanchine’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Furthering the magic and majesty of nature in full bloom during summer was the dancing of Oberon (Daniel Ulbricht) and Titania (Miriam Miller). The impossible quickness of Ulbricht’s petit allegro felt like the buzzing speed of hummingbird’s wings. Later on in the first act, peppered in this fast footwork were leaps up such that his whole body arched. Pleasantly mystified, I thought, “Where’s the momentum for that coming from?” Miller’s soft, yet assured flight in leaps and travel across the stage reminisced a fluttering butterfly, traveling flower to flower.

Another memorable section came with two ballerinas and one danseur, one ballerina in red and one in blue. One could see a symbolism here, red for fiery passion and blue for calm and contemplation. They played out comedic pantomime of drawing toward and away, illustrating the games and antics of courtship. A last memorable section in this act was a pas de deux with Bottom (Preston Chamblee) and Titania. As occurs somewhere in many Balanchine works, there was a comedic defiance of classical ballet norms here. Bottom, as a furry creature, danced with Titania, dressed elegantly in the classical norm. As she backbended, Puck somewhat clumsily took little shuffling steps to shift position and support her. I wasn’t the only one in the audience chuckling. It seems to have been one of those things funnier in the moment than it sounds, the nuances of physical comedy making much of it.

New York City Ballet in George Balanchine’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’. Photo by Erin Baiano.

The first part of the second act depicted a stately, ornate wedding. Slow steps forward, with pride and presence, transitioned into quick turns. This repeated sequence underscored the ritual formality within traditional weddings. A section of the stage filled with dancers contrasted the following coda section — solos and a pas de deux from Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar. I could see what was special in each structure — grandeur in the first and nuance in the second. Another special element coming soon was children dancing on in lines. Their turns zipped right around, and their focus never broke, revealing commendable maturity in their technique and performance ability for their seeming ages. Amidst the magical and fantastical, varied ages being present on stage added grounding realism.

Toward the final end of the ballet, lights flickered upstage, like fireflies in a meadow after dusk. A final magical image was Puck (Roman Mejia) flying high, other characters looking up at him. Humor, fun, magic, majesty — it can all be found at the intersection of Shakespeare and Balanchine. NYCB offered a very fine vehicle to this intersection, bringing technical command mixed with heart, humor and inventiveness.

By Kathryn Boland of Dance Informa.