This is our latest installment in “5 Things I Want to Tell Dancers”, a series with expert advice for dancers, choreographers and companies. Here, a top dance photographer explains how to get the images you need. Check back in the months ahead for more.

Getting great shots of dancers and dances is critical for social media and other publicity purposes, as well as for documentation. To find out how to do that, we went to Stephanie Berger, whose photography book, Merce Cunningham: Beyond the Perfect Stage, has just come out. For Berger, it’s the culmination of 25 years of producing vivid photographs of top groups — Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Mark Morris Dance Group, Trisha Brown Dance Company and many more — in the nation’s greatest performance venues. She has been the staff photographer for the Lincoln Center Festival since its inception in 1996 and works regularly for PBS, shooting hosts and casts for programs ranging from Downton Abbey to PBS Arts Festival.

#1. All dressed up.

A dress rehearsal called especially for photography is one of the best situations for a dance photographer, according to Berger. “Everyone is in costume, and the set and lighting are finished,” she says. “But because it’s a rehearsal, the photographer can get close to the performers and even ask for parts to be repeated.”

Stephanie Berger in front of her photo installation, Dancing in the Streets, at the LOOK3 Photo Festival, 2013. Photo courtesy of Berger.

When choreographers allow the photographers to re-stage a few sections just for the photos, that opens up more possibilities, Berger says. “Sometimes, we see a wonderful moment but know it won’t look as strong in the photograph unless, for example, the dancers are closer together or the lighting can be brought up,” she explains. “Let us ‘cheat’ a little on your behalf.”

Choreographers should also keep an open mind about where the photographer might shoot from, Berger advises. The wings can be a good place to find unexpected angles, for example. If it’s not possible to have the photographer at a dress rehearsal — perhaps because the tech isn’t finished — he or she can use a long (telephoto) lens to shoot a performance from the back of the theater, Berger says.

#2. In the beginning.

Shooting a dance that you have just started choreographing requires a bit of workaround, says Berger. Generally, this kind of session arises when a company needs publicity shots, even though the dance is unfinished. In that case, Berger suggests inviting the photographer to watch a rehearsal.

Choose a few of the best moments together, and let the photographer shoot them from a lot of different angles. “What you get may not look exactly like the final dance, but it’ll be strong and represent its energy,” Berger shares.

The Park Avenue Armory presents ‘Tree of Codes’, directed and choreographed by Wayne McGregor, performed by dancers from Paris Opera Ballet and Company Wayne McGregor. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

#3. Making dancers look great.

Dance photography is a frame around movement, says Berger. “Dance is always about moving, even when it’s still,” she adds. “If you allow the photographer to show that, the images will be exciting and engaging, which might mean not worrying about whether your dancers are always striking perfect poses. As a result, people will enjoy the photos and, by extension, will want to see your dance.” When choosing a dance photographer, look for someone whose work is filled with energy. “That is the most important attribute,” says Berger.

#4. Thinking outside the studio and theater.

Berger recommends discussing alternate locations with your photographer. “When I did the book about Merce, I found that the changing light in some of the spaces was so incredible, the shots became about that,” she recalls. Consider parks, industrial spaces, streetscapes and other places that will provide additional visual possibilities. Think about shooting behind-the-scenes material for another perspective on your work, she says.

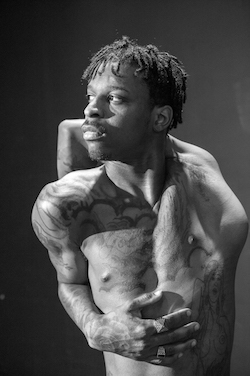

Derick Dashawn Unique Murreld AKA SLICC. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

#5. Rights and credits.

Be sure you and the photographer understand how the photos will be used in return for the fee. “In my case, I always retain the copyright but allow the dancer or company to use the photographs for whatever purposes they require — publicity, social media, to release to newspapers for use with reviews and so on,” Berger says. If you have the conversation, the situation will be clear.

Photo credits are very important to photographers, she says. “I ask that my name always be adjacent to the photos everywhere, even on social media,” she explains. “I want the photographs out there, but with my name next to them.”

Berger continues, “Dance photography is a collaboration. If all participants are communicating and working together, you’ll get great photos that pop, and everyone will be happy.”

By Stephanie Woodard of Dance Informa.

Photo (top): Brandon Collwes (jumping) of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company performs Beacon Event (2009) at Dia:Beacon in Beacon, NY. Photo by Stephanie Berger.